Bullying Prevention: Changing our Language, Modeling Empathy

Bullying Prevention: Changing our Language, Modeling Empathy

Rebecca Wenrich Wheeler - MA, MEd, CSAPC

Preventing bullying behavior among youth begins with adults. Recognizing the impact of language, school climate, and adult modeling are foundational to bullying prevention.

Language describing bullying behavior influences our perceptions on the preventable nature of bullying. The term anti-bullying is often misused when someone actually means bullying prevention. While, yes, we are against bullying, the term anti-bullying is reactive, as if bullying behavior is inevitable and unable to be prevented. All we can do is react when it happens. Prevention involves a shift in mindset, moving from reactive to proactive thinking.

The Youth Truth Survey is a national non-profit that researches bullying trends across the country. According to the survey, bullying rates vary widely across schools, with some reporting a low of 12% bullying and others a high of 59%. This data highlights the potential for preventing bullying behaviors, as the experiences students have in one school might be vastly different than students in another. The Youth Truth Survey reports the highest bullying rates in majority white schools; whereas, schools with more equally proportioned numbers of ethnic groups report lower bullying rates. Additionally middle school students report being bullied at higher rates than high school students (39% vs. 27%). “Understanding the range of student experiences across different campuses can help prioritize resources and interventions where they are needed most,” (YouthTruth).

Adults should avoid labeling youth as “bullies” and “victims”, as these labels tend to remain fixed and emphasize the false idea that bullying behavior is inevitable. According to stopbullying.gov when youth are labeled in these terms it may:

- Send the message that the child's behavior cannot change

- Fail to recognize the multiple roles children might play in different bullying situations

- Disregard other factors contributing to the behavior such as peer influence or school climate

Instead of calling a youth “bully” use “the youth who bullied”, and rather than calling a youth a “victim” say “youth who was bullied” (stopbullying.gov).

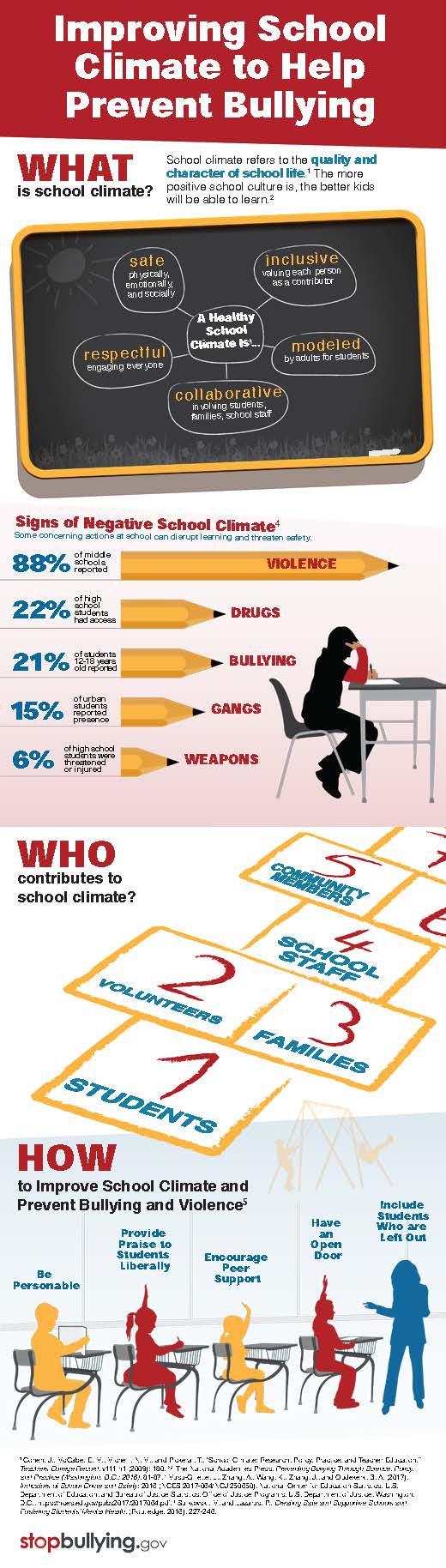

Next, promoting a positive school climate has been shown to decrease bullying behavior among youth. The National School Climate Center outlines five characteristics of a positive school environment:

Next, promoting a positive school climate has been shown to decrease bullying behavior among youth. The National School Climate Center outlines five characteristics of a positive school environment:

- Norms, values, and expectations that support people feeling socially, emotionally and physically safe.

- People are engaged and respected.

- Students, families, and educators work together to contribute to a shared school vision.

- Educators model and nurture attitudes that emphasize the benefits and satisfaction gained from learning.

- Each person contributes to the care of the school and physical environment.

Promoting a positive school climate begins by training both students and staff. Identifying and training student leaders to promote positive prosocial behaviors will help establish the social norm that bullying behavior will not be tolerated (Notar & Pagett, 2013). Teachers have reported lacking skills to effectively handle bullying behavior, and increased anxiety when they must do so (Notar & Pagett, 2013). Helping teachers learn how to recognize verbal and passive bullying and intervene properly will help prevent bullying behaviors from escalating. Additionally, training teachers to “manage student social dynamics and handle aggression with clear, consistent consequences will not only promote academic success, but also build relationships, trust, and a sense of community” (as quoted in Notar & Pagett, 2013). Also, teaching social skills helps to decrease bullying behavior. For instance, help the youth who was bullied determine if their reactions could be making the bullying behavior worse, for example crying in front of the youth who is the bully or walking a particular route home without a buddy (SAMSHA). Children who bully might need to increase problem-solving and anger management skills, or help “resisting the peer pressure to bully”, (SAMSHA).

Parents also play a role in preventing bullying behavior by modeling empathy, respect, and kindness toward others. Parents first model how to treat others by how they treat their own children. “When kids know they can count on their parents and caregivers for emotional and physical support, they are more likely to show empathy to others,” (Ellis, 2016). In addition, children are more likely to mimic a behavior if they see the behavior positively reinforced (Rymanowicz, 2015). When a negative behavior is rewarded over a positive behavior, the negative behavior is reinforced. For instance if a child hears an adult making a racial slur, and another adult laughs, what has the child learned? In contrast, what if the child hears the second adult calmly respond that the slur was offensive and ask the person to not use that language? Parents should help their children recognize biases and stereotypes and be able to talk about the negative feelings that surround those issues (Ellis, 2016)). When parents model conflict resolution and anger management, children will increase their capacity to handle similar challenges in their own life.

Works Cited

Ellis, R. (2016, November 09). How To Keep Children From Modeling Aggressive Adult Behavior.

Notar, C. E., & S. P. (2013). Adults Role in Bullying. Universal Journal of Educational Research,1(4), 294-297. doi:10.13189/ujer.2013.010403

Rymanowicz, K. (2015). Monkey see, monkey do: Model behavior in early childhood.

SAMSHA. The Role of Socializing Adults in Bullying Prevention. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

YouthTruth Student Survey. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

Teacher Resource: The Role of Socializing Adults in Bullying Prevention

We lack research on the role of socializing adults, other than parents and teachers, in preventing bullying and promoting healthy relationships among children and youth. This research gap reflects the previously held perspective that bullying is primarily a school problem. There is growing recognition that bullying can unfold in all of the contexts in which children and youth come together. There is a pressing need for research on the important role that other socializing adults play in promoting safe and healthy relationships.

The following guidelines for leaders working with children and youth have been developed based on the principles found here.

1. Lead By Example: Children watch adults’ behavior closely. If we model respectful and empathic behavior and positive conflict resolution strategies, then children are more likely to adopt similar behaviors in their peer relationships. On the other hand, if our interactions are critical, demeaning, or aggressive, how can we expect the children around us to behave any better? Think carefully about the words you choose and the way you behave.

2. Establish a Code of Conduct: Involve children and youth in developing a code of conduct about what they consider to be acceptable and unacceptable behavior during recreation activities. If children are responsible for creating a group policy around bullying, they are more likely to follow and enforce it with their friends. Post the code of conduct to remind children (and adults) about what will and will not be accepted in your organization.

3. Use Consequences that Teach: These are consequences that are designed to send the message that bullying is unacceptable while also providing support for children who bully to learn the skills and acquire the insights they are lacking. For example, a child who bullies may be asked to sit out of an activity and use that time to write a letter of apology or draw a picture of what it feels like to be bullied. Children who bully need help understanding the impact their behavior has on others. Read more methods here.

Featured Poe Program: #YouthCulture

Grade Level: Adults

Program Length: 2 hour workshop

The Poe Center’s #YouthCulture program is designed to empower parents and guardians by providing insight into the environment and culture around our youth. This 2 hour workshop explores how the developing adolescent brain shapes perceptions and behavior. All participants will receive a free packet of supportive materials and resources. Covered topics will include substance use, Internet safety, sexting, and healthy dating relationships. In addition we will explore ways to enhance parent-child communication.

Additional scheduling options consist of 90 minute modules:

1. Adolescent Brain Development and the Role of Social Media: Learn about current research on adolescent brain development and teen risk perception. Participants will also explore how a risk perception impacts a teen’s engagement with social media and Internet security.

2. Healthy Teen Relationships: Learn to recognize warning signs of unhealthy dating relationships and potential dating violence. In addition participants will learn current sexting statistics and trends as well as North Carolina laws.

3. Adolescent Brain Development and Addiction: Learn how early onset substance use affects the development of the adolescent brain and how substance use by teens might mask underlying mental health issues like anxiety and depression.

4. Navigating “The Talk”: Learn about resources and tools to assist you in developing and tailoring the talk with your teen about social media, teen relationships, and substance use.

Opioids 101

Learn about the growing concern of opioid use (prescription pain medicine and heroin) in our communities and how to recognize the risk factors, youth perception of risk, scope of the opiate problem, signs and symptoms, as well as action steps and resources to keep children from opioid use. Adults will receive relevant resources and information.

Find more information about #YouthCulture HERE!

Stigma: The Preventable Barrier to Care

Stigma: The Preventable Barrier to Mental Health Care

Rebecca Wheeler - MA, MEd, CSAPC

For people with mental health and substance use disorders, stigma is often a roadblock to treatment. A 2012 CDC report defines stigma as “negative attitudes and beliefs that motivate the general public to fear, reject, avoid, and discriminate against people with mental illness.” Three aspects of stigma: social isolation, self-stigma, and discrimination, decrease a person’s likelihood of seeking treatment. Stigma also reduces the public’s will to provide and legislate funding for mental health services. Even if services do exist, people may perceive a lack of services and thus not seek treatment.

The World Health Organization names mental health issues as the world’s “biggest economic burden,” costing nations $2.5 trillion in 2010 and an estimated $6 trillion by 2030 (Friedman 2014). Two-thirds of that cost is attributed to disability and a loss of work. In any given year, 26.2% of adults 18 and older experience a mental health disorder, but only 35% seek professional help (Friedman 2014). The outlook for young adults is bleaker, as only 18-34% seek help for a major depressive episode (Friedman 2014). Mental illness is common and can happen to anyone. Fighting stigma must be recognized as an important strategy for preventing negative outcomes for those with mental health and substance use disorders.

Social Isolation

Persons with mental health and substance use disorders often experience social isolation. From childhood, kids are taught to use words like “crazy” and “weird” to describe others whose behaviors are not considered the norm (Friedman 2014). Many adults perceive those with mental illness are dangerous; ideas often fueled by negative media and the idea that violent criminals are mentally ill (Friedman 2014). Fear increases social isolation as people avoid interacting with those labeled as “dangerous.” Even healthcare professionals might harbor these biases, which impacts care.

Persons with mental illness may socially isolate themselves to avoid embarrassment or disclosure. Some might believe that they should be able to handle problems without asking for help or have negative attitudes toward seeking help (Gulliver, et al. 2010). One review of 22 studies showed that stigma and embarrassment were the primary reasons for not seeking help (Friedman 2014). Such isolation tends to decrease a person’s sense of self-efficacy and decrease recovery outcomes.

Self-Stigma

Self-stigma is ‘felt’ even when discrimination is not present (Centers 2012). “People’s beliefs and attitudes toward mental illness also frame how they experience and express their own emotional problems and psychological distress and whether they disclose these symptoms and seek care,” (Centers 2012). People who already believe that those with mental illness are dangerous and burdens are more likely to internalize those stigmas when they experience their own personal mental health concerns (Watson, et al. 2007). People might avoid disclosing symptoms and adopt unhealthy behaviors to cope, such as substance misuse and eating disorders (Centers 2012). To avoid seeking help, people may alter “the meaning they attach to this distress, and in particular whether or not it is ‘normal’ in order to accommodate higher levels of distress and avoid seeking help” (Gulliver, et al. 2010). In other words, the person knows he or she is under distress, but justifies his or her feelings as ‘normal’, and determines professional help isn’t necessary.

Discrimination and Accessibility

Negative stereotypes may lead to discrimination and a lack of mental health treatment services. Stigma results in lower prioritization of public resources for mental health services. “People’s beliefs and attitudes toward mental illness set the stage for how they interact with, provide opportunities for, and help support a person with mental illness,” (Centers 2012). A 2012 study reported that the public was less willing to pay for prevention of mental illness than physical illness (Centers 2012). Surveys show the general public’s understanding of the biological causes of mental illness have improved; however, this understanding appears unrelated to improving negative perceptions (Centers 2012). In some cases, learning about biological causes increased negative perceptions of mental illness (Centers 2012). The biological knowledge “proved” that persons with mental illness are dangerous thus increased social isolation. Personal biases must be confronted when educating people with the facts.

According to a CDC report, over 80% of respondents felt that treatments for mental illness were effective, but only 35-67% felt people were sympathetic toward those with mental illnesses (Centers 2012). Persons with mental illness were even less likely to agree that the public was sympathetic. People in states with increased mental health services were the most likely to say treatment is effective and that people are sympathetic (Centers 2012). Accessibility to treatment not only improves health outcomes, but also decreases stigma.

People living in rural populations have greater concerns about accessibility to mental health services, and rightly so, as urban centers tend to have increased concentrations of mental health resources (Gulliver, et al. 2010). Additional barriers include a lack of transportation and high costs associated with care.

In a study of young adults, the perceived “quality” of school-based providers impacted whether or not youth asked for help. Youth reported concerns about confidentiality and fears counselors would overreact. Additionally, youth reported being uncomfortable talking to someone about mental health who also must enforce school rules. (Gulliver, et al. 2010)

Action Steps to Minimize Stigma

1. Make efforts to minimize personal bias. Engage in trainings that help to identify and manage your own bias toward mental illness (Friedman 2014).

2. Improve mental health literacy for youth and adults. Mental health literacy includes the “knowledge and beliefs that can aid in the recognition, management, or prevention of mental health disorders,” (Centers 2012).

3. Improve young adult mental health support. Build the emotional competence of young adults, promote a positive attitude about seeking help, and address the youth’s desire for self-reliance. Emotionally supporting a young person will increase a willingness to disclose when they need help (Gulliver, et al. 2010).

4. Encourage opportunities to engage in support groups. Identifying with a group of people who've had similar experiences increases self-esteem, reduces self-stigma, and helps individuals to know they are not alone. (Watson, et al. 2007)

References:

Friedman, M., PhD. (2014, May 13). The Stigma of Mental Illness Is Making Us Sicker.

5 Action Steps for Helping Someone in Emotional Pain

1. Ask: “Are you thinking about killing yourself?” It’s not an easy question but studies show that asking at-risk individuals if they are suicidal does not increase suicides or suicidal thoughts.

2. Keep them safe: Reducing a suicidal person’s access to highly lethal items or places is an important part of suicide prevention. While this is not always easy, asking if the at-risk person has a plan and removing or disabling the lethal means can make a difference.

3. Be there: Listen carefully and learn what the individual is thinking and feeling. Findings suggest acknowledging and talking about suicide may in fact reduce rather than increase suicidal thoughts.

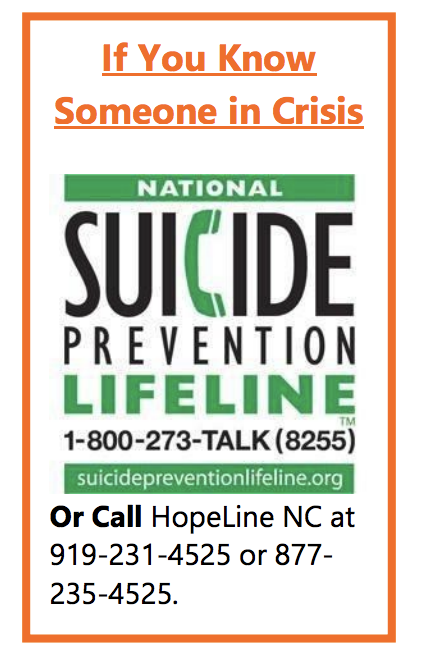

4. Help them connect: Save the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s number in your phone so it’s there when you need it: 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You can also help make a connection with a trusted individual like a family member, friend, spiritual advisor, or mental health professional.

5. Stay Connected: Staying in touch after a crisis or after being discharged from care can make a difference. Studies have shown the number of suicide deaths goes down when someone follows up with the at-risk person (e.g. phone calls, etc.).

Additional Resources on Organizational Suicide Prevention Best Practices

http://www.togethertolive.ca/policies-and-protocols

http://www.togethertolive.ca/best-practices-risk-management

See a complete list of resources here.

Featured Poe Program: Youth Mental Health Training

Featured Poe Program: Youth Mental Health Training

Grade Level: Adults

Program Length: September 26th, 2018 | 8 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. | Poe Center for Health Education

Youth Mental Health First Aid is designed to teach parents, family members, caregivers, teachers, school staff, peers, neighbors, health and human services workers, and other caring citizens how to help a adolescent (age 12-18) who is  experiencing a mental health or addictions challenge or is in crisis. Youth Mental Health First Aid is primarily designed for adults who regularly interact with young people. The course introduces common mental health challenges for youth, reviews typical adolescent development, and teaches a 5-step action plan for how to help young people in both crisis and non-crisis situations. Topics covered include anxiety, depression, substance use, disorders in which psychosis may occur, disruptive behavior disorders (including AD/HD), and eating disorders.

experiencing a mental health or addictions challenge or is in crisis. Youth Mental Health First Aid is primarily designed for adults who regularly interact with young people. The course introduces common mental health challenges for youth, reviews typical adolescent development, and teaches a 5-step action plan for how to help young people in both crisis and non-crisis situations. Topics covered include anxiety, depression, substance use, disorders in which psychosis may occur, disruptive behavior disorders (including AD/HD), and eating disorders.

Register here for this one-time session or search for similar trainings here.

Learn more about our Annual Meeting & Luncheon Conferences here.

Celebrating Differences: Five lessons for teaching kids acceptance

Celebrating Differences: Five lessons for teaching kids acceptance

Chris Corsi – Health Educator

As a children's health educator who uses a wheelchair, students frequently ask me lots of questions about my disability. It's their way of acknowledging and valuing me. Plus they simply want to know more. From the typical “Why do you have a wheelchair?" to the more thoughtful “How do you drive? Can you push the pedals?”, the volume of questions can feel as though I spend as much time teaching about myself as I do health topics.

Children's curiosity knows no bounds. By answering my students' questions, I hope to help them see people with disabilities as more whole people. However, sometimes the questions portray falsehoods that kids may have already begun to internalize. For example, some questions imply that disabled people are sad or unable to do things for themselves.

This issue extends beyond disability. Children often have questions when they encounter people they see as different from themselves, be that difference based on ability, race, gender, sexual orientation, appearance, or origin. This is perfectly natural, and it creates an opportunity to engage kids in important conversations. While sometimes these conversations seem tough, it’s an important opportunity to help kids actively choose to be inclusive of people who (at first!) seem unlike them.

Tips on how to teach youth to accept, respect, and value differences:

1) Challenge the idea of “normal.”

Generally, people are treated differently because they’re seen as “the other.” For children, anything outside of “normal” may seem undesirable. It's helpful to challenge the idea of “normal” to see past differences. All of us are born unique with different likes and preferences, so there is no one way to be "normal."

Child: “That person sounds so weird! Why is that?”

Adult: “Well, they have an accent. They might be from somewhere else. That doesn’t make them weird - just different, and different isn’t bad.”

Teaching children to see similarities is important, but the goal is not to eliminate our differences. By acknowledging differences and similarities simultaneously, kids will find they can learn from people who aren't like them. Studies show that ignoring differences actually makes discrimination worse. This article from The Atlantic delves deep into the research behind implicit bias and how to break it down.

2) Teach children to not be afraid to ask hard questions. Don’t shy away from hard answers.

It can be embarrassing to hear your child ask questions about "different" people, but questions often come from a place of innocent curiosity. It’s best to be as honest as possible, and it's okay to say “I don’t know.” Scholastic advises “children often interpret a lack of response to mean that it's not acceptable to talk about differences. If you're unsure about what to say, try: ‘I need to think about your question and talk to you later.’ Or, you can always go back to a child and say: ‘Yesterday you asked me a question… Let's talk about it.’” By answering honestly, you create opportunities for more conversations about differences which also shows your child that it’s okay to ask respectful questions.

3) Cultivate empathy and community.

It can be hard for kids to see themselves in people who are different, which is why it’s important to encourage children to empathize and help them get to know people unlike themselves. Review your child's media and related influences. Does it include diverse individuals and oppose cultural stereotypes? When kids see "different" people in a positive light, they are better prepared to challenge harmful stereotypes. It's helpful to encourage children to make friends who aren’t like them. According to contact theory, one of the best ways to improve intergroup relations is simply interpersonal contact. Getting to know people different from oneself leads to reduced prejudice and increased understanding.

4) Know your child is listening.

Is may seem easier to shield children from challenging issues, such as racism, bigotry, or oppression. But the reality is children will be confronted with these issues through the media, in day-to-day conversations, or with their peers. Generally, young people are able to recognize when somebody is being treated differently. Seize the moment to model empathy and make it clear that it’s unacceptable to use slurs, to use identity as an insult, or to treat somebody worse because they are different.

Be thoughtful about your own words, too. Young people mirror what they hear.

5) Understand intent.

While adults may understand using nuanced language in reference to groups of people, children may not yet have the language or skill set to do so. “Generally, children want to know why people are different, what this means, and how those differences relate to them. Remember that children's questions and comments are a way for them to gather information about aspects of their identity and usually do not stem from bias or prejudice,” writes Scholastic. If a child says something potentially offensive, it probably isn't intended to be harmful. It's best to correct the underlying misconceptions behind their statement or engage them in a conversation about how their words could hurt feelings.

These are just a few ways to begin teaching young people how to accept and value others for their difference. For many, the process may need to begin with challenging your own biases. Ultimately, the goal is to create a more tolerant and compassionate culture for current and future generations.

Resources:

Here are some other articles that may offer some additional assistance in addressing issues of difference with children:

Teaching Diversity: A Place to Begin by Scholastic

6 Ways to Teach Your Kids About Disabilities

Tips for Talking to Kids About Gender and Sexual Orientation

How To Talk About Diversity With Your Kids

Sometimes You're A Caterpillar – Educational video targeted to middle-school students about diversity

References:

https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/teaching-diversity-place-begin-0/

http://www.apa.org/monitor/nov01/contact.aspx

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/05/unconscious-bias-training/525405/

Featured Poe Program: The Alphabet of Bullying

Grade Level: 6th – 8th

Program Length: Four 60-minute sessions

Sessions Include:

Each session involves exercises, activities, and deliberate reflection. Students are challenged to “dig deep” into themselves and overcome real and perceived pressures in order to do the right thing. Each session includes reflection time with journaling responses to thought-provoking prompts, and there is a pledge at the end of all of the sessions, describing what is expected of those who have been through the program. Learn more.

Call us to schedule a program today.